Broadly, I am interested in computational astrophysics as it pertains to: galaxy evolution, star formation, feedback from supermassive black holes or supernovae, satellite galaxies, and large-scale structure. My more recent work has focused on understanding the distribution of dust in the Universe.

My specialty is working with cosmological, magnetohydrodynamical simulations. Galaxy evolution occurs over such large timescales that it is impossible for humans to observe directly. Cosmological simulations act as a pseudo-laboratory, allowing scientists to input physical theories and hypothesis and output a mock Universe. How closely these simulated universes matches the one we observe tells us about how well we understand (or don’t) the input physics. But the comparison of simulated and observed universes is far from trivial. A large part of my work is processing simulated data in a way that makes it comparable to observed data.

The majority of my work has been conducted with the results of the IllustrisTNG suite of simulations.

Active Project: Circumgalactic Dust

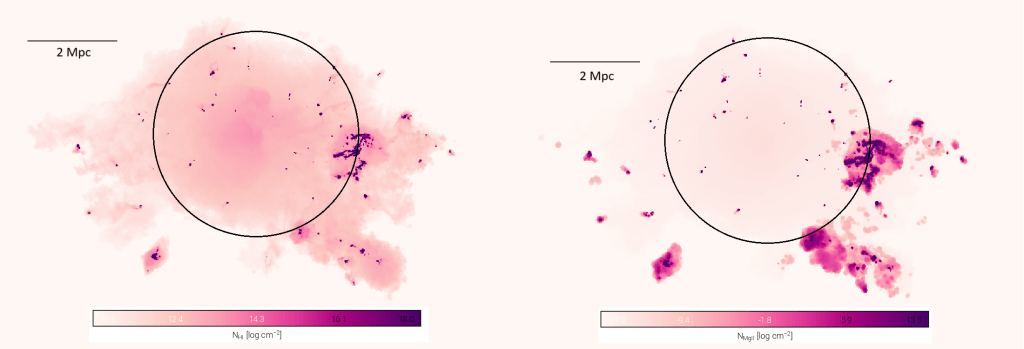

Dust in the Universe reddens and dims light from distant objects, but the amount of this dust and its evolution with cosmic time is poorly constrained. But interpreting the light we receive from distant objects is one of the few ways we can collect real data about astrophysics. So it is critical that we understand how much dust is out there. My postdoctoral work at Northeastern University focused on applying post-processed prescriptions for “in-painting” dust onto the TNG300 simulation, in order to ultimately compare the distribution of dust around galaxies to results from observations. For more on the observational side of this project, see this article by my collaborator at NU, Jacqueline McCleary.

The TNG simulations track extensive information about stars, gas, dust, dark matter, and supermassive black holes. However, the simulation does not directly model dust. Thus, I have developed and continue to improve upon a model that infers the amount of dust present in the simulation based on properties of the gas. This project is, in part, motivated by a large gap in understanding regarding the properties of circumgalactic dust, which results in large uncertainties regarding many aspects of the dust model I have developed. Like many models of complex phenomenon, we suspect that this model will have to revised and adapted as we obtain results from the model and compare them to observations.

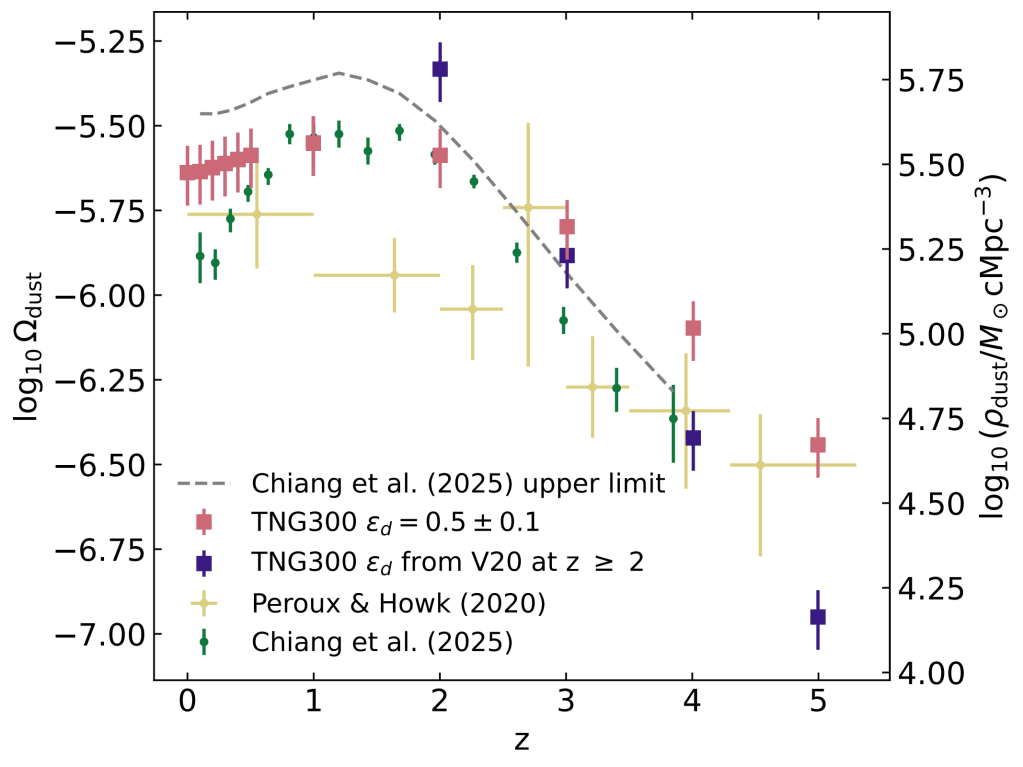

Our current model is very simplistic, but results in a surprisingly good agreement with observations when we look at the evolution of cosmic dust density as a function of redshift:

Active Project: Satellite Galaxies and Magnetic Fields

Inspired by a work that found a similar phenomenon in a different simulation, Alexander Poulin (an NU undergrad) and I looked into the average magnetic field strength of satellite galaxies in TNG100. We found that the magnetic fields of satellite galaxies (those that are orbiting more massive central galaxies) are about 10 times stronger than the magnetic fields of central galaxies of similar masses! (Link to RNAAS paper.)

This is super strange and weird and I want to know more!!! I just need time (or some undergraduate help) to look into this further.

Resolved Star Formation in TNG100 Galaxies

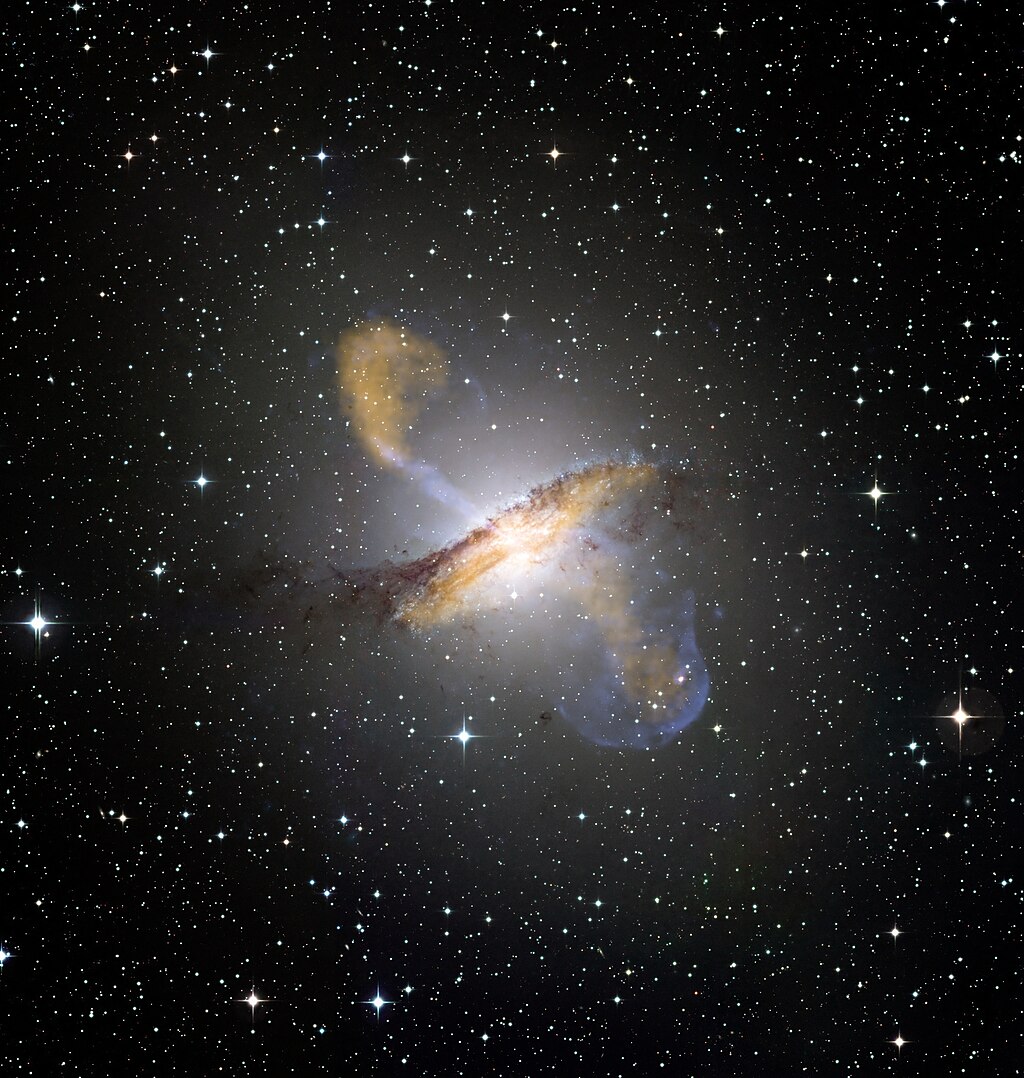

One aspect of galaxy evolution that has been challenging to model is the cessation of star formation in galaxies, or quenching. In the observed universe, most galaxies are either actively star forming, or quenched, with few in between. Early simulations were not able to reproduce populations of galaxies with similar properties, largely because star formation in simulated galaxies was over-efficient at early times. Modern simulations, like TNG100, have resolved this problem by heating or removing the gas in the disk of the galaxy (preventing it from cooling enough to collapse and form a star) with processes called ‘feedback.’ Feedback generally comes in the form of winds and energy from supernovae or the central supermassive black hole.

Credit: ESO/WFI (Optical); MPIfR/ESO/APEX/A.Weiss et al. (Submillimetre); NASA/CXC/CfA/R.Kraft et al. (X-ray) – http://www.eso.org/public/images/eso0903a/

Feedback is challenging to implement in cosmological simulations because the energy is generated on scales much smaller than the resolution of the simulation. Instead, computational astrophysics has tested different modes of approximating the effects of feedback. As the TNG100 simulation now reproduces the global properties of observed galaxies (e.g. the star formation rate of whole galaxies), I am testing how well the feedback models are able to reproduce local (i.e., resolved) properties of galaxies.

To do this, I am investigating both whether the simulation reproduces an observed trend known as the resolved star formation main sequence (rSFMS) and whether it reproduces the observed radial distribution of star formation within certain populations of galaxies.

This project was the majority of my dissertation and the data set of spatially resolved TNG100 galaxies is in use for other projects.

Distribution of Satellite Galaxies in the TNG100 Simulation

Credit: ESO/S. Brunier – ESO

Simulations test the models astronomers use to understand what we observe, but there are parts of the universe that can’t be seen with a telescope. Dark matter does not give off any light and does not interact with baryonic matter in a normal way. We can only see the gravitational effect that dark matter has on galaxies. This leads us to believe that the dark matter resides in a spherical halo around galaxies.

To further understand dark matter, it is important to have a better grasp on how it is distributed in these halos. One suggestion is that the dark matter can be traced by how satellite galaxies are distributed around their host. Like the Magellenic clouds to our Milky Way galaxy, other galaxies have smaller ones orbiting them.

I have looked at satellite galaxies that were formed in the TNG100 sand found that they cannot be used to trace the dark matter distribution of their hosts.

The Dusty Torus Around Active Galactic Nuclei

Credit: Credit: C.M. Urry & P. Padovani.

The summer after my second year I began work on a computational project investigating the dusty torus surrounding active galactic nuclei (AGN). A then-graduate student, Dr. Triana Almeyda, had developed a Python code called TORMAC to simulate the reverberation response of the dusty torus. These simulated light curves could be compared to observed light curves to determine the size and shape of the torus, which can’t be resolved by current telescopes. That summer and following winter break I spent running the simulations for various sizes and shapes of tori and then comparing the synthetic light curves. That work also involved testing new versions of the code as different shadowing effects were considered.

One effect that hadn’t been considered was that of sublimation at the inner radius. The first version of TORMAC destroyed dust clouds that had reached the sublimation temperature of the interstellar grain mix. This didn’t account for the time sublimation takes or the larger carbon grains that won’t sublimate until higher temperatures. This problem was the focus of the REU I did the summer after my junior year and my senior research project.

To implement this into TORMAC, I had to use a radiative transfer Fortran code developed by our collaborators to make a grid emission responses from carbon clouds. TORMAC can interpolate within these grids to find the emission from an ensemble of clouds. With the carbon-dominated clouds, TORMAC could compute the reverberation response of a two-component torus. The hot inner edge of the torus dominates the response in the near infrared. This means that when using near-IR data for reverberation mapping, it is important to consider the inner torus where dust is not fully sublimated.

My Brief Foray Into Surface Science

In my second year at RIT, I conducted research with Prof. Michael Pierce in a surface science laboratory equipped with an x-ray diffractometer and ultra-high vacuum system. Using this equipment, I probed the surface composition and alignment of various samples. As part of this research, I traveled to the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratory to use x-ray diffraction to determine how applied voltage changes the surface of an electrolyte. My first summer project dabbled in instrumentation, attempting to build a device that would deposit thin films using radio-frequency induction heating. The ultimate failure of this endeavor cemented my desire to work in a computational field.